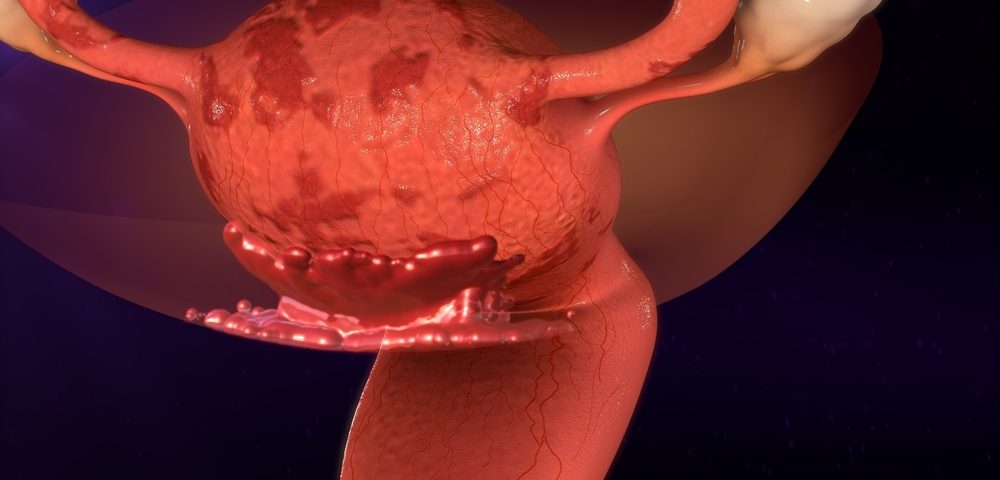

A researcher from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Center for Gynepathology Research (CGR) has created a three-dimensional tissue culturing system that could aid the study and potential diagnosis of endometriosis.

The 3D model supports distinct layers of different cell types — sourced from endometrial biopsies — that can be exposed to hormones such as estrogen and progesterone, in a way that mimics the month-long menstrual cycle.

The bioengineering student behind the creation, Christi Cook, said she developed the model to help scientists understand the ways hormones impact the tissue that lines the uterus.

“My goal has been to develop better in vitro model systems so that we can understand some of the endometrial pathologies that women face,” Cook said in a news story written by aken a couple years to develop the model system, and we’re now beginning to understand and use them to study things like inflammation and how that impacts hormone responsiveness.”

MIT launched its Center for Gynepathology Research in 2009 to improve the understanding of conditions that predominantly affect women. The center is co-led by scientific director Linda Griffith of the MIT bioengineering department and Dr. Keith Isaacson of Harvard Medical School.

The CGR encourages researchers to apply tools from bioengineering to study a topic previously confined to traditional methods of biological analysis. Many gynecological conditions are characterized by changes in hormone response of the uterus cells; endometriosis, adenomyosis or leiomyoma are all examples.

With endometriosis, current available treatments begin with a first-line treatment of oral contraceptives; however, not all women can tolerate such therapies, and they are not always effective. The next step is usually hormone antagonists, which block cells’ ability to sense hormones.

But “these can have nasty side effects — it’s like a fake menopause, so this isn’t ideal,” Cook said. A third option is surgery, to remove the misplaced endometrial cells. But this may also not be completely effective.

“There’s no perfect way to treat this disease right now,” Cook said. “What works for someone might not work for someone else and we still don’t know why.”

The CGR has been working to advance knowledge of endometriosis with other research groups as well, such as the MIT iGEM team, with whom it has created a synthetic biology tool for diagnosing endometriosis.

Another project was in collaboration with MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), where the center helped develop an app that lets patients track the day-to-day impact of their disease, whether it is endometriosis or another condition.

The CGR also helped collect and analyze the data, comparing it to patients’ biopsies stored in the lab. Researchers found that, even though endometriosis is currently classified based on the size of misplaced cellular growths, symptom severity doesn’t always necessarily match the apparent severity of the disease stage.

“Maybe there are different types of endometriosis, but right now we’re lumping it as one single disease,” Cook suggested, adding that day-to-day symptoms of endometriosis might be divided into subsets, which could lead research into new classifications of endometriosis.