Endometriosis — an illness that causes infertility, cramping and severe menstrual pain — is more common than either breast cancer or diabetes. Yet, unlike those two diseases, endometriosis is still widely under-diagnosed and deeply misunderstood, says Noémie Elhadad, an associate professor of biomedical informatics at New York’s Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC).

Elhadad should know; at the age of 13, she herself was diagnosed with the disease. A computer scientist by training, she left her native France after completing undergraduate studies and has a Ph.D from Columbia in artificial intelligence.

“I’ve been in the biomedical domain for the past 10 years,” she told Endometriosis News in a phone interview from New York. “Most of my work is not on patient-generated data but rather looking at clinical data from doctors and discovering patterns of disease progression and predicting adverse outcomes.”

In February 2016, Elhadad branched out into something new. She and her team launched Citizen Endo — an ambitious project she said is “all about engaging women with endometriosis in building data sets for research, and having them be partners in asking questions about what could be happening within their bodies.”

The 18-month venture is budgeted at around $300,000, with most of that funded internally by Columbia, though Elhadad said Citizen Endo recently got a small, undisclosed grant from the Endometriosis Foundation of America (EFA). For its first nine months, the Citizen Endo team at CUMC focused on designing a tool that would help collect vital information from patients.

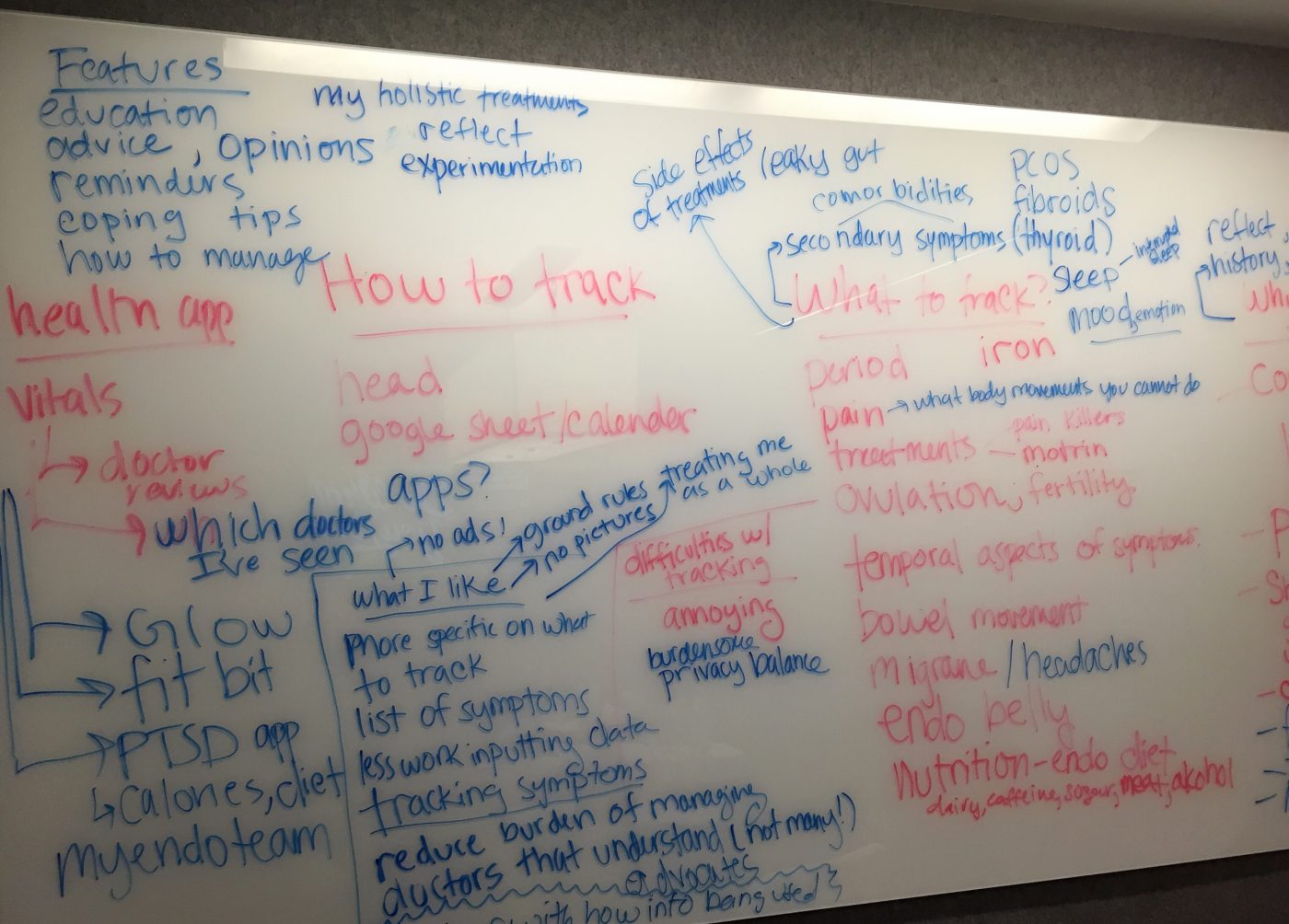

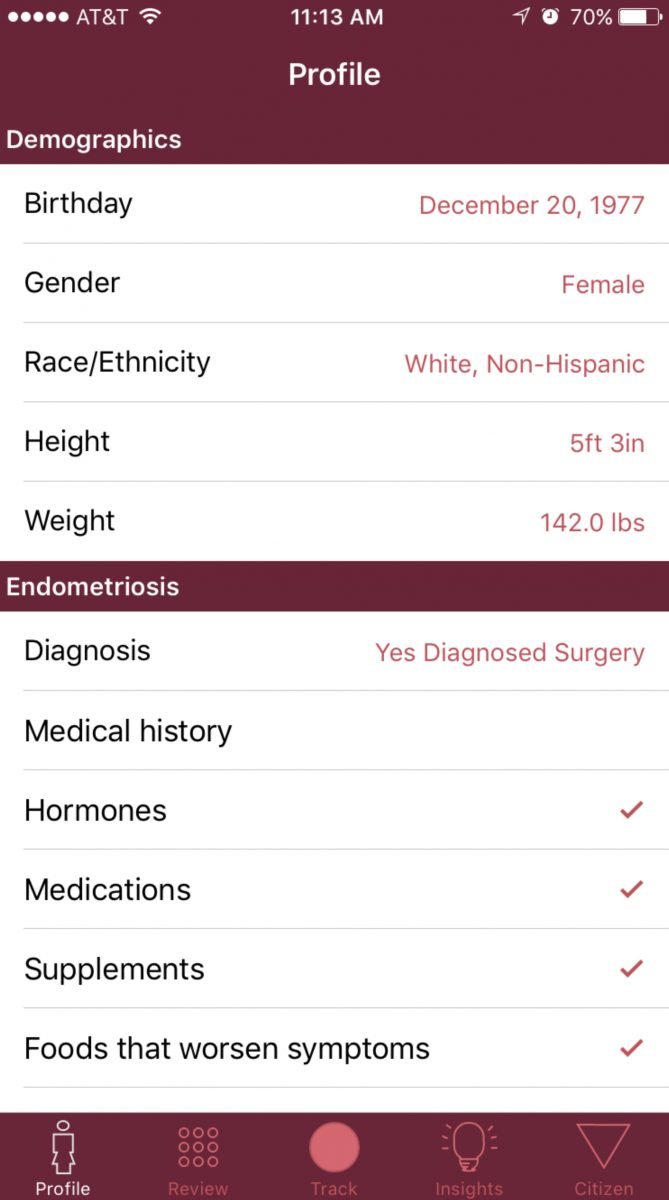

“We would identify patients who wanted to talk about it, then interview them and do surveys so we could understand what would be useful to track. We spent the rest of the time building an app that would allow women to track their endometriosis,” she said. “Since we launched the app in December 2016, we’ve been collecting data and changing it as we’ve gotten more and more feedback.”

The project — which posts frequent updates on both Twitter and Instagram — got off the ground with focus groups of 30 women each. It then moved to online surveys with 500 to 800 women and, after launching the app itself, known as Phendo, it has expanded to about 2,000 women actually using the app at least once during their menstrual cycles.

But that’s not nearly enough for the project to realize its full potential — and Elhadad is now in a drive to bring knowledge of this app, and its importance to endometriosis research and disease understanding, to thousands more.

“I’m used to looking at millions of patients at a time,” Elhadad said. “That’s why I’m frustrated, because even though 2,000 is way more than what you can get through traditional means of recruiting people, like observational studies, I want 10,000 women by the end of next year.”

Besides Elhadad, the Citizen Endo team consists of doctoral student Mollie McKillop and project manager Sylvia English, both full-time staffers, as well as two volunteer team members, Hannah Ephraim and Jillian Jatres.

At present, women are participating from at least 40 countries. But because the app is in English, most of its users are from English-speaking nations such as the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand — as well as Northern European countries where English is at least widely spoken. Next month, Elhadad will travel to Israel in an effort to expand her project’s reach to the Middle East.

Another limit is more technological. The free app now runs only on iPhones, though the grant from the New York-based EFA will help finance its soon-to-be migration to Android-enabled smartphones.

“What we’re trying to optimize for is as many women as possible, and as many days tracked for each woman as possible,” Elhadad said. “The big innovation with our app is that many surveys out there are very static. They ask things like, ‘how have you been feeling in the past three months?’

“Our goal is to gather experiences of endometriosis throughout the cycle — not by asking patients to recall things, but as it happens, so we can have more of a sense of the disease. The point is to do some statistical analysis and identify patterns on how things change throughout a menstrual cycle. The more data we have on an individual across time, and the more women we have, the better.”

Elhadad estimates that endometriosis affects 10 percent of all women — even though most published studies put that number at around 6 percent.

Elhadad estimates that endometriosis affects 10 percent of all women — even though most published studies put that number at around 6 percent.

“There is a lot of under-diagnosis happening, but because it’s so prevalent, there must be some subgroups to the disease. That’s why we want a lot of examples of women, so we can identify them statistically,” she said.

She cited both scientific and cultural reasons for under-diagnosis of the illness.

“It’s a disease we still don’t understand. It presents differently in different women, so there’s no real typical patient, but rather groups of typical patients,” she said. “There’s also no biomarker for it, so there’s no test you can take. People have been searching for one for awhile, but so far no luck.”

She added: “The way it’s diagnosed is pretty invasive: laparoscopy with general anesthesia. That kind of weeds out a lot of the potential for being diagnosed early — especially when you think it’s a disease that starts with puberty.”

The second reason, said Elhadad, is more cultural.

“It’s a disease that’s about pain in women, and one of those chronic diseases that has vague symptoms — pain and exhaustion related to the menstrual cycle. There’s a very strong stigma to this,” she said. “The patients themselves don’t know what’s normal. There’s an idea that women’s pain is all in their heads. There are a whole set of diseases like that. For example, with fibromyalgia, there’s a debate if it’s even a real disease.”

Elhadad said she hopes Phendo will be available to Android users by the end of this summer.

“We know there will be more women using it, because we have twice as many people who want the Android version,” she said, “so this will be very good for us.”