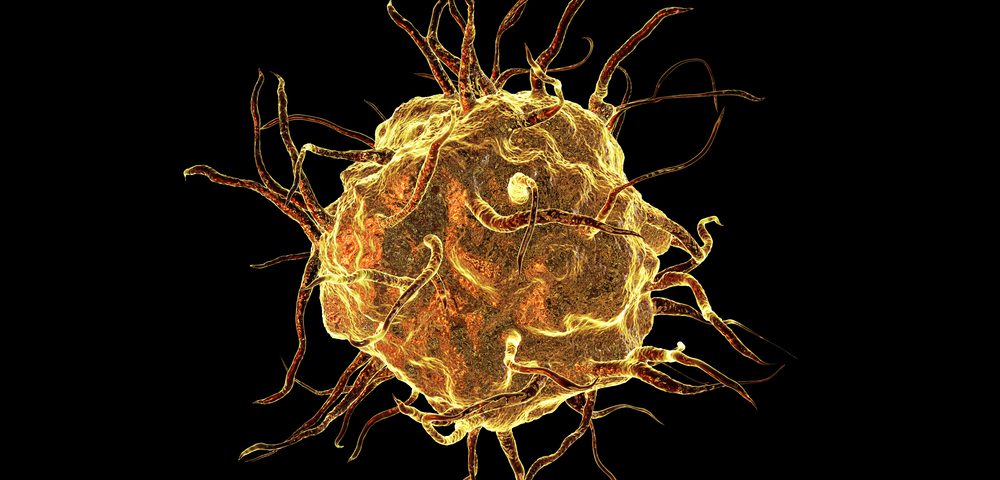

Immune cells likely contribute to endometriosis, researchers argued in a recent review that looked at current evidence showing the immune system may be involved in the disease.

The review, published in The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, showed it’s not possible to determine whether these cells and their actions cause the development of endometriosis, or if they enhance disease processes that were initiated by other factors.

Nevertheless, learning more about how immune cells impact disease processes may allow researchers to develop new treatments for the condition, researchers from the University of Tokyo in Japan argued.

The review was titled “Involvement of immune cells in the pathogenesis of endometriosis.”

Studies show that inflammatory cells called neutrophils are found in higher numbers in the abdominal cavity of patients with endometriosis compared to healthy people.

These cells secrete a variety of factors to increase inflammation and attract other immune cells. The levels of these factors are also increased in patients, the review noted.

However, researchers are not sure how these cells contribute to the disease. Scientists assume the inflammation they cause contributes to the formation or worsening of lesions.

One study in a mouse model of endometriosis suggested neutrophils were at work in the initial processes leading to disease, but were not required for its progression, researchers said.

Another cell type called macrophages are also likely involved. Just like neutrophils, macrophage levels are increased in the gut cavity, and animal experiments suggest they may play a role in both endometriosis development and progression.

These cells also promote an inflammatory environment. In addition, they boost the growth of blood vessels into the endometriosis lesion. Macrophage cells, which normally work to engulf invading microbes or cell debris, lose some of this capacity — which is called called phagocytosis.

Experiments also show that macrophages can directly stimulate endometriosis cell growth. Other studies show that, in endometriosis patients, macrophages take on similar characteristics as those seen in people with cancer. Researchers also believe these cells are involved in the generation of pain in endometriosis.

Meanwhile, so-called NK-cells, which can directly kill infected or tumorous cells, appear less active in endometriosis patients. This observation has led researchers to suggest that activating them might be a way to treat the condition. Mouse studies confirm that this idea could be worth pursuing, researchers said. Similar approaches are used in cancer therapies.

T-cells, which exist in various pro- or anti-inflammatory types, also appear affected in the disease. Studies show that inflammatory variants dominate, which further drives inflammation.

Studies of immune cells in endometriosis have, so far, given scientists a crude picture of what may be going on, the Japanese team said. However, this picture underscores the importance of additional research into the linked disease processes, they wrote, particularly as such insights may lead to new endometriosis treatments.